10 Effective Methods to Soothe an Anxious Brain

By Due Quach, guest contributor

1. Accept that anxiety is biological

1. Accept that anxiety is biological

The first step in managing anxiety in a healthier manner is to make peace with the fact that having anxiety is natural and normal. According to evolutionary psychology, human psychological traits like anxiety exist because they serve a function. Anxiety signals that we believe the outcome of a situation in which there are factors beyond our control, is very important to our survival, social status, happiness, or well-being. Anxiety is the result of the body entering state of stress (AKA sympathetic arousal) and releasing extra energy to tackle a challenge that requires us to leave our comfort zone without any guarantee of success. Nevertheless, too much energy can make us feel restless and agitated. It can make a racing mind speed even faster so our focus becomes super scattered. The key is to learn how to harness this energy rather than get sidetracked by trying to get rid of it.

It may also be helpful to make a distinction between fear in its primal form and anxiety. Fear arises when we experience a dangerous life-threatening situation that activates the amygdala that helps us detect threats. Anxiety arises when the dopamine circuitry or reward system of the brain gets attached to achieving a specific outcome and the possibility that the outcome will not turn out the way we want activates the amygdala. Thus, anxiety levels corresponds to the degree of desire and attachment we feel rather than to the degree of danger we are in. For instance, even when there is a 99% chance that the outcome will be fine, when we focus on the 1% chance that a different outcome may happen (especially one which we consider a disaster), we can still feel overwhelming anxiety.

2. Consume stress hormones by burning restless energy

2. Consume stress hormones by burning restless energy

Stress hormones like cortisol kick the body into high gear to run from danger, so a moderate intensity cardiovascular work-out that burns this extra energy is the easiest way to bring your body back into equilibrium. I want to put an emphasis on the word “moderate” because exercising too intensely can increase stress hormones and lead to inflammation and the risk of injury. Thirty to forty-five minutes of jogging, cycling, or swimming usually does the trick. As an added bonus, exercise also increases the amount of oxygenated blood flowing to the prefrontal cortex of the brain and releases endorphins which lift up our mood.

In addition, mindful movement exercises are great for helping us shift from being stuck in our heads worrying about the future or ruminating about the past to being grounded in our bodies in the present moment. Yoga, qi gong exercises, dance classes have a restorative effect on the parasympathetic nervous system and help integrate mind, heart, and body.

3. Do slow, deep breathing to activate the parasympathetic system

3. Do slow, deep breathing to activate the parasympathetic system

The easiest way to “turn on” the parasympathetic nervous system is through taking slow, deep breaths. The idea is to slow your breathing cycle (a complete inhale and exhale) by inhaling slowly until you fill your lungs to full capacity and then exhaling slowly until you empty your lungs and create a vacuum. One simple and subtle way to do this is by using a 6-3-6-3 breathing cycle, which means you inhale for a count of six seconds, hold your breath for three seconds, exhale for a count of six seconds and hold your breath for three seconds. Doing this for two to five minutes will calm the sympathetic nervous system and make it easier to sleep.

When you are in a private space, you can try an alternate nostril breathing technique used in many yoga traditions, which is said to rebalance the autonomic nervous system. The recommended breathing cycle patterns usually involve exhaling for about twice as long as the inhaling, which makes sense because our heart rate tends to slow when we exhale. Start by using a finger to close your right nostril, then breathe in through your left nostril for a count of 4 seconds and hold your breath for 4 seconds. Then switch by closing your left nostril and breathe out through your right nostril for 8 seconds. Breathe in through your right nostril for 4 seconds and hold your breath for 4 seconds. Now switch by closing your right nostril and breathe out through your left nostril for 8 seconds, and begin again. Feel free to skip holding your breath if it feels uncomfortable or to play with shortening or lengthening the breathing cycle.

4. Notice when you are catastrophizing

4. Notice when you are catastrophizing

When researchers studied the mindset and behaviors of pessimists versus optimists, they created a shorthand called the 3 P’s to summarize the pattern they found. Essentially, pessimists tend to make a negative event or setback feel catastrophic by perceiving it as pervasive (“everything in my life sucks”), permanent (“things will always be like this”) and personal (“it’s my fault; I am terrible”), whereas optimists do the opposite by perceiving it as isolated (“the rest of my life is fine”), temporary (“today was a bad day but tomorrow will be better”), and impersonal (“the other team got lucky and won”).

The researchers also found that a pessimist could learn optimism by noticing when their mind is catastrophizing using the 3 P’s and then proactively reframe the event as isolated, temporary and impersonal. I can personally testify that using this method has helped me notice and break many catastrophizing patterns. To learn more, I recommend reading Martin Seligman’s Learned Optimism.

5. Tend and befriend

5. Tend and befriend

It is widely known that stress elevates levels of cortisol and other stress hormones that activate the freeze-flight-fight response. However, stress can also elevate oxytocin, known as the “cuddle hormone” because it prompts us to build social bonds. This “tend-and-befriend response” (as it was named by scientists who discovered it) sets off a regenerating cascade that offsets the damaging effects of stress hormones, such as inflammation. According to Kelly McGonigal in The Upside of Stress, “caring for others triggers the biology of courage and creates hope.” She also advises: “Whether you are overwhelmed by your own stress or the suffering of others, the way to find hope is to connect, not to escape.” McGonigal adds, “In any situation where you feel powerless, doing something to support others can help you sustain your motivation and optimism.”

Many studies have found that people who volunteer to do community service tend to be healthier, feel happier and more connected, and live longer than those who don’t, in part because altruistic acts of kindness and compassion boost oxytocin levels. In addition, something as simple as writing down or sharing what you are sincerely grateful for can elevate levels of oxytocin.

6. Revise unrealistic beliefs and expectations

6. Revise unrealistic beliefs and expectations

Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) works by helping people understand that having realistic beliefs and expectations enables them to deal with setbacks and challenges in a healthy manner. In contrast, when people have unrealistic beliefs or expectations, they can have a very negative reaction when a situation stirs up their unrealistic beliefs or expectations.

Here are a few examples of self-defeating irrational beliefs that result in anxiety and suffering:

- Smart people effortlessly ace every exam (since I had to work hard to get a B+ on this test, I must not be very smart).

- I have to be perfect to be worthy of love and respect (since I am not perfect, I am not lovable).

- Successful people know what they are doing and are confident and in control (since I feel insecure that I don’t know what I am doing—I must be a fraud).

Freeing yourself from this form of self-inflicted suffering requires developing the ability to look at the beliefs that underlie your negative reactions and to compassionately revise these beliefs and expectations to be more in line with reality. I learned to do this by using the ABCDE method that Martin Seligman shares in Learned Optimism. Here is a quick overview.

- A - Adversity: What happened (who, what, when, where)

- B - Beliefs: My beliefs regarding A or what I say in my head about A

- C - Consequences: How I feel and act as a result of B

- D - Disputation: Making sure I reality check B and revise my beliefs to be more in line with reality and more constructive (look at evidence and facts that contradict B, seek alternative views, and discern whether believing and reinforcing B is useful or limiting)

- E - Energization: The shift in my energy levels and feelings when I revise B

7. Focus on concrete actions within your control

7. Focus on concrete actions within your control

I started to use this method to manage anxiety during college after reading Stephen Covey’s The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.

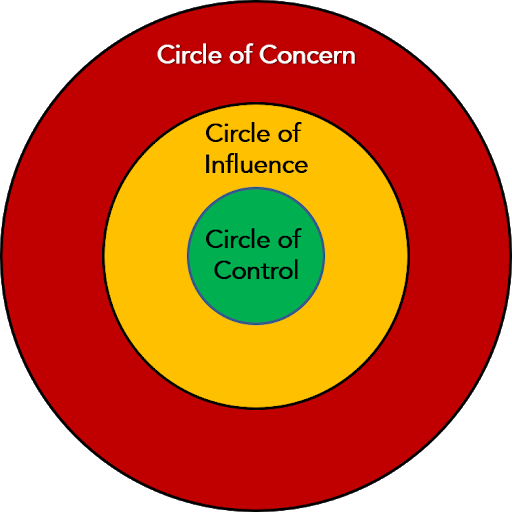

What stood out most for me was a framework Covey shared containing 3 concentric circles. The largest one is called the Circle of Concern, as it contains all the things we are concerned about. The middle one is called the Circle of Influence, as it contains all the actions we can take to influence people to address our concerns. The smallest one is called the Circle of Control, as it contains all the actions directly within our control that we can take to address our concerns.

Covey explained that we get the highest return on our time and energy by focusing on things within our Circle of Control. When we focus our energy and time in the outer ring on things beyond our influence and control, we naturally feel anxious and disempowered. For the things within our Circle of Influence, we should do our best to communicate our ideas and concerns, but must accept that we can’t control other people. What anybody who makes decisions actually decides and does is beyond our control.

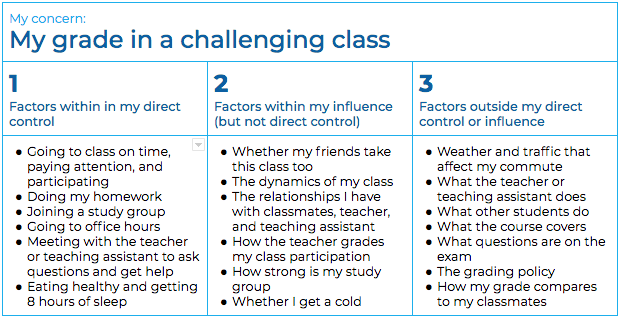

I then adapted this framework into a tool to clarify the things I could actually do about something I was concerned (and anxious) about. I simply make a table with 3 columns and label them: 1. Factors within my direct control, 2. Factors within my influence, and 3. Factors outside my direct control or influence.” Then I list the factors in each column. See example below.

Once I have grouped these factors into these 3 categories, I try to focus my energy on things I listed in Column 1. After that, whenever I find that I still am still stressed out about something in Column 3, I try to add anything I can do to influence it in Column 2 and anything I can do to directly address it in Column 1. Then I do what I can, and let go.

Doing this exercise helps me minimize how much energy I waste worrying and beating myself up over things I couldn’t realistically do anything about. By discerning between what I can influence but not control and constructively channeling my energy towards actions within my control, I feel a lot more productive and have a lot more peace of mind.

8. Visualize yourself overcoming the negative outcome you want to avoid

8. Visualize yourself overcoming the negative outcome you want to avoid

In many cases, the outcome we are anxious about is not as bad as we anticipate it will be in our minds. For example, when I was in college, the idea of graduating from Harvard without a job or even a clue how I would pay my student loans filled me with so much dread, I felt like I would rather die than go through that. That worry set off many sleepless nights and panic attacks. Eventually, I did graduate without a job, and my life wasn’t as horrible as I had imagined. After school, I actually had more time to ask people to have coffee and share about their career paths and eventually got the advice and guidance I needed to apply for jobs, make a good impression during interviews, and start my career.

That experience taught me that one way I can free myself from the grip of anxiety is to use a visualization exercise to build my confidence that I really can handle the negative outcome I am anxious about avoiding. I start by describing the outcome that I want to avoid. Then I imagine it actually coming to pass and what that would actually feel like in my body. Next, I walk through all the ways I can pick myself up and move forward with my life.

To build equanimity like a muscle, it can be very helpful to create a safe container to experience a scenario you dread in small doses. For instance, I can get very anxious about rejection. Sometimes, I deliberately put myself in a situation that can lead to rejection, such as asking for something that is a bit difficult, so I can experience that rejection really isn’t that unbearable and that it’s not that hard to bounce back. Furthermore, unexpected positive outcomes can unfold. When a person wasn’t able to say yes, they sometimes offered a solution that was actually better than what I originally asked for.

9. Write down what Brain 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 tell you

9. Write down what Brain 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 tell you

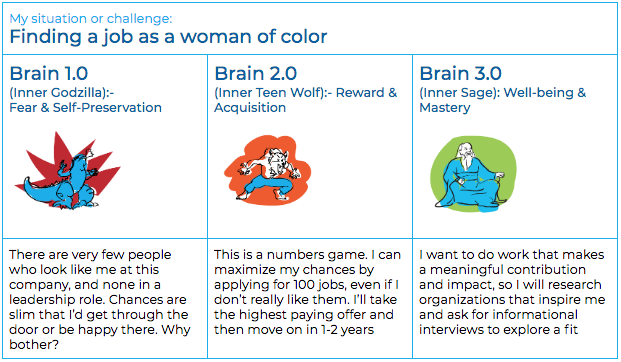

The simultaneous or rapid sequential activation of different neural networks can be like hearing a cacophony of voices in our head, which contradict each other and trigger conflicting emotions. This swirl of brain activity can leave us feeling stuck, frustrated, and confused about how to move forward.

When I feel this way, I find it helpful to take a moment to reflect and sort out how each part of my brain (I’ve identified them below as Brain 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0) sees the situation or challenge I’m facing. I simply create a table with three columns. On the left, I write down what Brain 1.0 (my Inner Godzilla) says and advises me to do. In the middle, I write down what Brain 2.0 (my Inner Teen Wolf) says and advises me to do. On the right, I write down what Brain 3.0 (my Inner Sage) says and advises me to do. Once it’s on paper, it becomes more obvious that Brain 3.0 gives me the best advice for moving forward. See example below.

10. Connect to a greater purpose and take small steps toward it

10. Connect to a greater purpose and take small steps toward it

Kelly McGonigal’s The Upside of Stress shares research on how people transform stress and anxiety into a challenge response by seeing a greater meaning and social purpose for undergoing adversity. Reframing anxiety in this way turns on beneficial biological mechanisms, such as the tend-and-befriend response, that enable people to harness the energy unleashed by the stress cascade to improve performance and concentration under pressure, to build social support and strengthen relationships, and to make a positive impact on the larger community. To learn more, I recommend reading McGonigal’s book.

When I meditate on my feelings of anxiety, I see that what’s really driving my distress is a desire for more control and predictability. At the core, I get anxious when I have doubts about why I should do something, my ability to rise to the challenge, and the willingness of other people to help and support me. Therefore, I help my mind to accept that uncertainty and unpredictability is woven into life and to connect the challenge to a greater purpose. In addition, I try to remember that throughout history, human beings in all cultures have found the inner strength to rise to challenges and support each other through very difficult transitions.

I also find it helpful to use this quote from Nelson Mandela as a mantra: “May your choices reflect your hopes, not your fears.” This quote helps me redirect my attention away from my anxieties to focus on aligning my choices to the outcomes I want. Now when I feel anxious, I see it as a signal that I really care about something. I then reflect on why it matters to me, and why it’s worth taking the risk to do something even if the outcome is uncertain and unpredictable. I then identify the actions within my control and influence I can take while accepting that the actual outcome is out of my hands. I have faith that if it is meant to be, it will unfold and that even if things turn out differently, I will still grow through the experience. I do my best to trust that whatever happens, the universe will connect me to people who will help me create a path. I take a leap of faith and a big breath, and then step forward, one baby step at a time.

Whenever you feel anxious, please experiment with these techniques as a toolkit for managing anxiety. You will likely find that for different situations, some of these tools are more effective than others. Lastly, your brain is unique so please feel free to adapt these exercises to work better with how your brain functions.

Due Quach is the founder and CEO of Calm Clarity and co-founder and Chair of the Collective Success Network. She is also the author of Calm Clarity: How to Use Science to Rewire Your Brain for Greater Wisdom, Fulfillment, and Joy. She is Mindful Leader’s neuroscience expert and teaches part of our CWMF course.

A version of this article was originally published in October of 2019

7 comments

Absolutely Awesome ! Love it 😍

Fantastic!

Great article that helps us redirect the positive energy in decision making!

Thank you for this rich collection of practical actions to live the life we intend to! I will be sharing it with my circles.

Love Due's work. Such important information and techniques, so well and simply explained. I'll be sharing it too.

Thank you for your observations and suggestions. I believe that much anxiety is created by feelings of powerlessness and fears of abandonment, each of which many of us have experienced -- not just worried about -- over the past couple of years of the pandemic.

I am a health coach. I spend part of everyday reading about or education people on stress management techniques. This is one of the best articles I have seen on the topic. Often, the articles are just 'fluff' or too scientific. This gives concrete ideas with just enough science to support.

Leave a comment