The Future of Compassionate Care Work: Beyond the Heroic Paradigm

By Deirdre Guthrie, guest contributor

“We burn out not because we don’t care, but because we don’t grieve.”

- Dr. Rachel Naomi Remen, a pioneer in humanizing medicine

Caring professions, such as education, healthcare, social work, and humanitarian development, are based on relationship-based service where workers expend high levels of emotional labor. While care-work is vital to any healthy society, as recent events have made abundantly clear, it continues to be undervalued and, for those on the lower brackets of care-work such as elder and childcare (1), underpaid. As a consequence, care-work is plagued by high rates of vicarious trauma, turnover, and burnout with its overlapping dimensions of exhaustion, ineffectiveness, and cynicism.

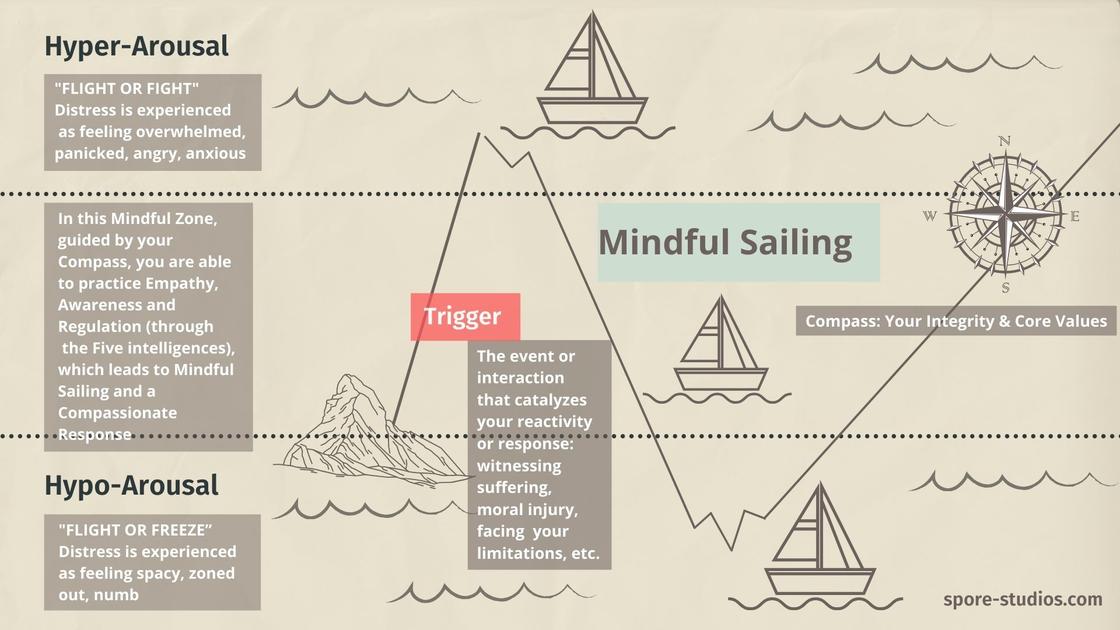

Those who are “called” to this work are both keenly sensitive to the pain or suffering of others and also compelled to alleviate such suffering. And while having a vocation is psychologically protective in terms of wellbeing, in that it instills a sense of meaning and purpose in one’s life, “call” also makes these jobs “high stakes” pursuits because so much of one’s core values and identity are wrapped up in work. The challenge, as Kelly McGonigal writes in The Upside of Stress: Why Stress is Good for You, and how to Get Good at it…, is how to tap into our human strengths of courage, connection and growth when we experience stress and stay within our “window of tolerance” so we may respond appropriately.

Mindfulness in the Caring Encounter

“Catch the Moment; Make a Choice.”

- Janet Friedman

“Every moment has a choice, and every choice has an impact.”

- Julia Butterfly Hill

Mindfulness as an experiential practice can help care workers approach their service with healthy boundaries as a form of “accompaniment” where one is committed to “walking with” others on their healing or learning journey with presence and resilience. It can also help workers become aware of when they are attaching their identity and wellbeing to an outcome that is out of their control.

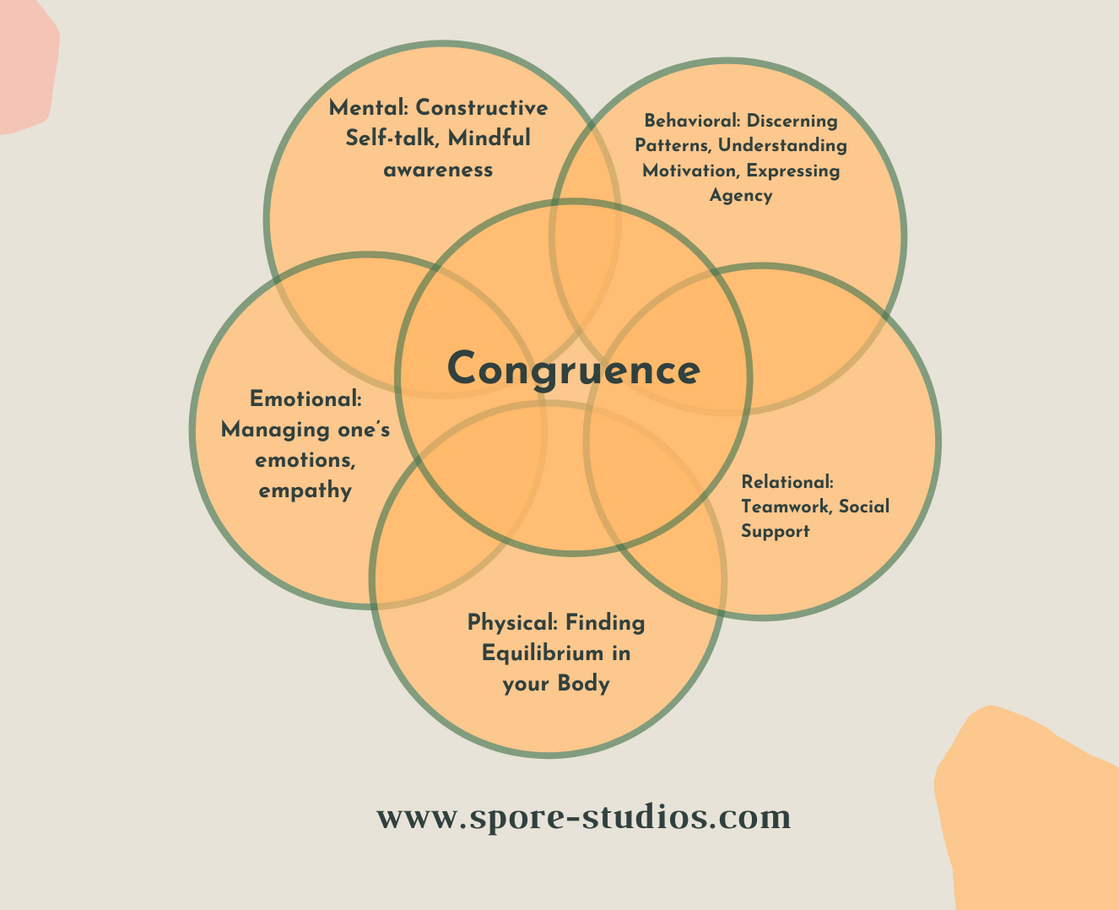

Incorporating mindfulness practices into learning paradigms is now a well documented best practice in strengthening one’s self-awareness. Yet, when trauma and high-stress loads are prolonged (as they are for care-workers and for so many of us now), mindfulness must be complemented with the development of mental, emotional, physical, behavioral, and relational intelligences through skills that regulate the survival brain and nervous system.

These intelligences are deeply interwoven in our intra-personal and inter-personal encounters. When our thoughts, feelings, body language and behavior align, we experience greater personal congruence, which allows us to respond and communicate more effectively in any relationship.

Mindfulness as a compassionate practice of moment-by-moment awareness of our thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, and surrounding environment provides the foundation of developing these intelligences and regulatory capacities.

Yet in order to move from dysregulation to resilience, individuals must widen their window of tolerance to stress in a way that is trauma-informed, particularly those with a history of chronic pain, depression, substance abuse, depression, anxiety or PTSD. Often this may mean shorter exercises that involve a body-based component, so as not to exacerbate an individual’s symptoms. Bessel Van der Kolk MD is a leading expert on how such therapies can tame the body’s trauma response.

As a tool for creating space to process lived experience in real time, mindfulness that brings care workers into regulation, that “mindful zone” of tolerance, can help them experience inevitable limitations or setbacks so they might better be equipped to accept, struggle or overcome them. With these intelligences developed and aligned, care-workers can better weather periods of sustained uncertainty and struggle with problems that may exceed their knowledge or skill-set.

If they’re able to regulate their emotions so that they are responsive and not reactive, they can witness suffering and attend compassionately to those who need their service, without being attached to the outcome in a way that leads to burnout. And, according to Roshi Joan Halifax, who has worked to develop tools to prevent burnout and secondary trauma in clinicians and hospice worker for decades, instead of compassion resulting in “fatigue”, compassion can serve as “a wellspring of resilience as we allow our natural impulse to care for another to become a source of nourishment rather than depletion."

When triggered by witnessing suffering, moral injury or distress, or personal limitation, compassion, guided by the ethical compass of our core values or integrity, can keep us sailing within that optimal zone where we can be responsive.

Combined with body-based regulation, Roshi Halifax’s G.R.A.C.E. model offers those in relationship-based service “a simple and efficient way to open to their patient's experience, to stay centered in the presence of suffering, and to develop the capacity to respond with compassion.”

When care-organisational leaders endorse, model, fund, and give space for the involvement of a trauma-informed mindful approach in the care-workplace, they help their staff become more resilient. Let’s support those who have endured unprecedented levels of chronic stress and unresolved trauma in 2020 move toward post-traumatic growth, healing and restoration in 2021. This means moving beyond the “hero” paradigm and creating organisational cultures that allow for capacity-building in acceptance, connection, adaptation, awareness, perseverance, and grit.

Download a free Caregiving resource based on this article here.

It's quite possible to use G.R.A.C.E. in your everyday interactions and allow it to help you cultivate more compassion in your own life. Here's how to do it. The G.R.A.C.E. model has five elements:

- Gathering attention: focus, grounding, balance

- Recalling intention: the resource of motivation

- Attuning to self/other: affective resonance

- Considering: what will serve

- Engaging: ethical enactment, then ending

You can use the following detailed description of each element as a script for your own G.R.A.C.E. practice:

- Gather your attention.

Pause, breathe in, give yourself time to get grounded. Invite yourself to be present and embodied by sensing into a place of stability in your body. You can focus your attention on the breath, for example, or on a neutral part of the body, like the soles of your feet or your hands as they rest on each other. You can also bring your attention to a phrase or an object. You can use this moment of gathering your attention to interrupt your assumptions and expectations and to allow yourself to relax and be present.

- Recall your intention.

Remember what your life is really about, that is to act with integrity and respect the integrity in all those whom you encounter. Remember that your intention is to help others and serve others and to open your heart to the world. This "touch-in" can happen in a moment. Your motivation keeps you on track, morally grounded, and connected to your highest values.

- Attune by first checking in with yourself, then whomever you are interacting with.

First notice what's going on in your own mind and body. Then, sense into the experience of whom you are with; sense into what the other person is saying, especially emotional cues: voice tone, body language. Sense without judgment. This is an active process of inquiry, first involving yourself, then the other person. Open a space in which the encounter can unfold, in which you are present for whatever may arise, in yourself and in the other person. How you notice the other person, how you acknowledge the other person, how the other person notices you and acknowledges you... all constitute a kind of mutual exchange. The richer you make this mutual exchange, the more there is the capacity for unfolding.

- Consider what will really serve the other person by being truly present for this one and letting insights arise.

As the encounter with the other person unfolds, notice what the other person might be offering in this moment. What are you sensing, seeing, learning? Ask yourself: What will really serve here? Draw on your expertise, knowledge, and experience, and at the same time, be open to seeing things in a fresh way. This is a diagnostic step, and as well, the insights you have may fall outside of a predictable category. Don't jump to conclusions too quickly.

- Engage, enact ethically. Then end the interaction and allow for emergence of the next step.

*Also check out this beautiful Care package for Caregivers, an offering of poetry, podcasts and meditations curated by Onbeing.

Notes:

(1) Some doctors–those that provide easily measured and reimbursable specialty services–earn high salaries. Public health specialists and primary care doctors sit much lower on an earnings spectrum bracketed on the bottom by child care and elder care workers, with nurses and teachers in between. Most care workers pay a penalty relative to others with the same education and experience.

Deirdre Guthrie, Ph.D., is the author of two chapters in Ethnographic Approaches to Health and Wellbeing Research (Routledge Press, 2020) and co-author of a 2019 Wellbeing at Work survey of Laureate organisations who won the Hilton Humanitarian award. She is a Mindful Leader Certified Workplace Mindfulness Facilitator and currently works as Research Manager on the organisational exploratory program of The Wellbeing Project, a catalyst organisation that supports the inner development of change-makers.

More from the author: You can learn more about her upcoming course on Compassionate Wisdom (January 18, 2021) here and view her workplace packages here.

Click here to sign up for our newsletter to stay up to date, get special offers, curated articles, free videos & more.

0 comments

Leave a comment